Visualizing the Space of IP Addresses

I’ve been learning about IPv6, and I built a visualization tool to compare its IP addresses with IPv4. The difference between the two is striking.

IP (Internet Protocol) is the system for transferring and routing data across the Internet. You may have heard of IP addresses, which are the numbers that are assigned to each computer or device so that data is sent to the right place. Their purpose is similar to that of postal addresses for regular mail.

IPv4, the most common variety in use today, allows for about 4.3 billion possible addresses. That sounds like a lot, but there are now 5.4 billion people online and we’re actually running out of addresses. It’s already taken a lot of engineering work to accomodate more users than addresses, and the problem is only going to get worse.

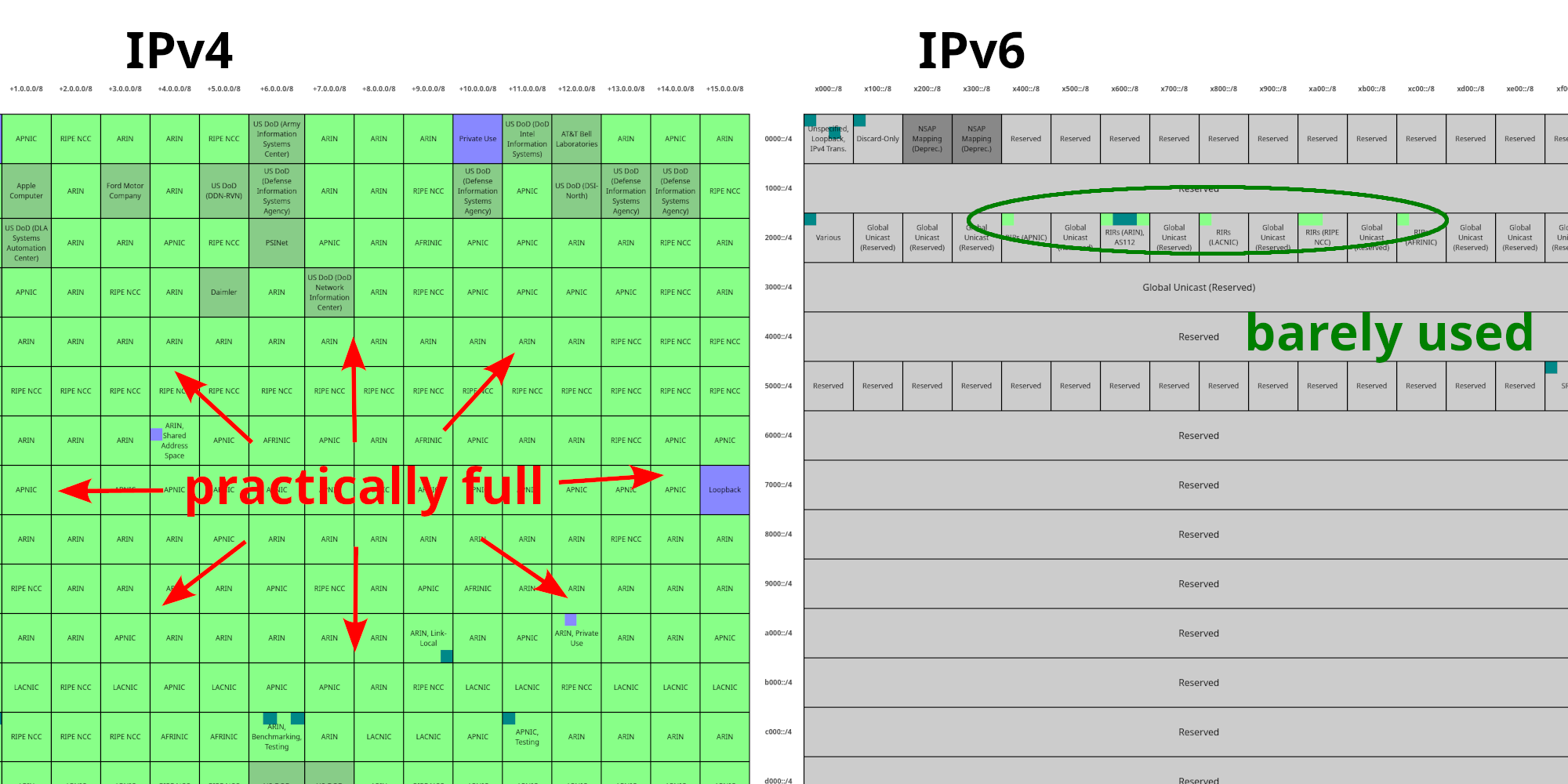

The solution is IPv6, which offers far more addresses than IPv4. Just how many more? The raw number is easy enough to quote: over 340 undecillion (34 followed by 37 zeros). But that might be difficult to put into perspective (and some argue that it’s misleading), so I decided to find out how the “space” of IP addresses is actually used. The result is two different visualizations, one for IPv4 and one for IPv6.

The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) designates ranges of IP addresses for different purposes, based on prefixes. (Continuing with the postal address analogy, this is similar to how many countries designate postal code prefixes to different regions. For example, this is how it’s done in the US.) In my visualizations, I use different colors to represent different functions: green for addresses on the public Internet, blue for special purposes, teal for mixed use, and gray for unassigned or reserved ranges.

The IPv4 address space is full of green, as most of it is already designated for public addresses. On the other hand, the IPv6 address space is almost empty, with only a few smaller ranges allocated along with some special-purpose ranges here and there.

Those “smaller” IPv6 ranges aren’t really smaller though. The takeaway is that the entire IPv6 address space is so much bigger such that just a handful of these smaller ranges is enough for the world’s needs. Even if we needed ten times as many in the future it still wouldn’t be a problem. This is why IPv6 is the way of the future. I’ve already enabled it on my home network (thanks to an ISP with good IPv6 connectivity) and I hope it continues to be adopted.